1. “Unbelievable” (1990). When Under the Red Sky came out in the fall of 1990, critics (with the exception of the ever perspicacious Robert Christgau) rushed to outdo each other in heaping invectives upon it. Ironically, it was with “Unbelievable,” an apocalyptically rumblin’, explosive blues rocker, that someone at NPR’s All Things Considered chose to conclude Ken Tucker’s unequivocally negative Red Sky review, thus making Tucker’s assessment--and by extension those of his fellow travelers as well--seem almost, well, unbelievable. In retrospect, the only explanation for Under the Red Sky’s instant unpopularity is that it followed Oh Mercy, which just one year earlier had been hailed as proof that Dylan could not only come back but also come back all the way. Understandably, folks wanted more where that came from. Instead, they got its opposite. Replacing the atmospherically skeletal spookiness provided by Daniel Lanois was a hard, Wilbury-Twisting gloss provided by Don and David Was. Replacing Oh Mercy’s brooding lyrics awash in familiar Dylanesque archetypes were warped nursery rhymes like “Cat’s in the Well” and “Wiggle Wiggle.” A vaguely Judeo-Christian religiosity persisted courtesy of the rollickingly rambunctious “God Knows,” but compared to the downright prayerful nature of Oh Mercy’s “Ring Them Bells,” “What Good Am I?,” and “Shooting Star,” Dylan seemed to be taking even that by-now-to-be-expected strand of his post-conversion music with a grain of sand. Dylan himself has disparaged the album, saying in essence that he felt he wasn’t giving the album his all because he was simultaneously involved with making the Traveling Wilburys’ Volume Three. Yet, at the time, the Was Bros. had nothing but praise for his work ethic. And certainly their decision to bring an ever-rotating cast of characters to the sessions no doubt fanned the flame of spontaneity toward which the moth of Dylan’s productivity had often been drawn. But back to “Unbelievable”: You can see the writing on the wall inviting trouble. And although the lyrics essentially comprise a compressed catalogue of every negative judgment that Dylan has ever made about our gone-wrong world, his critique of pseudo-psychiatry stands out. “Every brain is civilized,” he growls. “Every nerve is analyzed.” That’s “is civilized,” by the way, as in made to submit to simplification, classification, categorization, and finalization. It’s as certain that such a collective brain will inevitably explode as it is that Dylan should hope the pieces wouldn’t fall on him.

2. “Ugliest Girl in the World” (1988). Not counting most of his contributions to The Basement Tapes, this song is one of the few sheer laugh riots in Dylan’s oeuvre. As for who wrote what in this uproarious Dylan/Robert Hunter co-composition, this much can be sure: Dylan wrote “I don't mean to say that she got nothing goin'. / She got a weird sense of humor that's all her own.” He had, after all, told Rolling Stone a few years earlier--speaking on the topic of why there aren’t more women rock-and-rollers--that Joni Mitchell “has a weird sense of rhythm that’s all her own.” Of all the “ugly” songs that threatened to merit an entire genre of their own in the years leading up to the new millennium (e.g., Gillette’s “Mr. Personality,” Fleming & John’s “Ugly Girl”), this one was hands-down the least beholden to the finger-wagging legalism of the burgeoning sensitivity police--and entirely in character given Dylan’s Biograph-interview insistence that a woman could be in a wheelchair for all he cared as long as her voice breathed soul.

3. “Union Sundown” (1983). Lest we forget, only one verse of this smoldering ahead-of-its-time anti-NAFTA Infidels cut is about “unions.” The rest is about the “Union,” i.e., what came to be known as the United States of America after the Northern gods and generals secured a surrender from Robert E. Lee after the War Between the States had run its course. Of course, in Dylan’s mind, the two are connected. One can almost see him walking into a Walmart, turning an ashtray over, seeing a sticker that says “Made in China” and thinking that mankind has invented his doom. Yet something in the furiously forward motion of this indignantly rocking track says he knows that doom is not the end, not as long as one can laugh at the roll call of sweat-shop countries that Dylan trots out herein at his black-humor best. But back to China (full disclosure: where I currently live and where just last week I bought a bootleg DVD of No Direction Home for $1.50): Dylan doesn’t mention it at all. Maybe, somewhere deep in his bones, he knew he’d perform there someday and encore with the most impassioned “Forever Young”s of his career. Seriously, track down and listen to the Beijing 2011 bootlegs. They’ll make you cry.

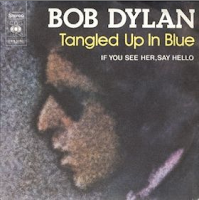

4. “Up to Me” (1974). It’s just as well that this song was left off the official Blood on the Tracks. Stellar though it is, its qualities (multi-perspective description, characters out the wazoo, flashes of fortune-cookie wisdom) would’ve most likely seemed redundant or like too much of a good thing considering that they already existed in abundance in “Tangled Up in Blue” and “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts.” Its sharply etched verbal and musical delineation sure lit up the third disc of Biograph though, coming as it did between the on-the-waters-bread-casting “Caribbean Wind” and the hornier-than thou “Baby, I’m in the Mood for You.” The Sermon on the Mount, of course, would in five years’ time amount to a lot more than what the broken glass reflects, but for now Dylan was content to remain on the other side of that as-yet-unshattered mirror and rummage through a bag of tricks that stretched all the way back to “Girl from the North Country” (cf. “Up to Me”’s last verse). Someday--maybe--he’d remember to forget.

5. “The Usual” (1987). This isn’t a Bob Dylan song; it’s a John Hiatt song that Dylan recorded for the soundtrack of perhaps the most disastrous film in which he ever starred. But the lyrics are unmistakably Dylanesque: “Sixty cigarettes a day because I’m nervous” (eighty according to Don’t Look Back but close enough); “I give her everything, but she refused it” (he gave her his heart, but she wanted his soul); “Look at the shape I’m in” (Lord, you don’t know it); “Fifty thousand kisses later, she was a housewife” (been there done Sara, with Carolyn Dennis well on her way); “I used to be a good boy, / livin’ the good life” (he was a clean-cut kid, but they made a killer out of him). No wonder he gravitated toward Hiatt’s sentiments. As for the line that asks “Where’s my pearls, where’s my swine?,” it could almost pass for the property of Jesus.

.png)

.png)

.png)